If you ever plan to spend more than a day in the great outdoors, the ability to confidently and accurately read a map will be invaluable. There's a lot more to it, though, than it may seem at first glance.

In this guide, we'll review the fundamental tools and methods of basic map reading. If you can master these skills, you should be able to read any land map well enough to get where you need to go.

Tools You'll Need

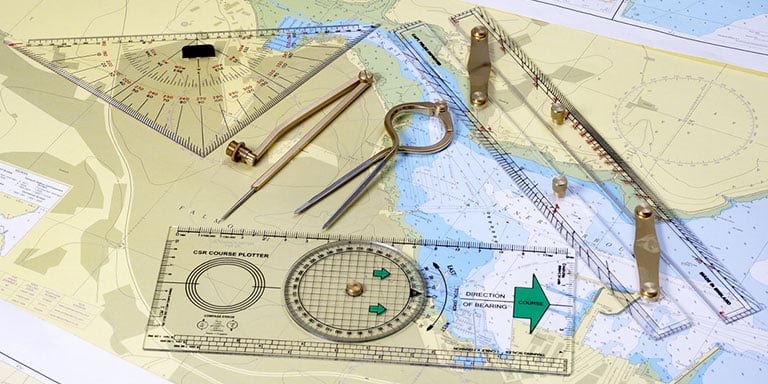

With practice, you can learn to read a map without any tools, but you'll always sacrifice some accuracy doing it that way. When first learning, or when precision is paramount, you'll need a few basic items.

- Topographic map: Of course, you'll need a map to read. A topographic map is a specific kind of map designed to aid in cross-country land navigation

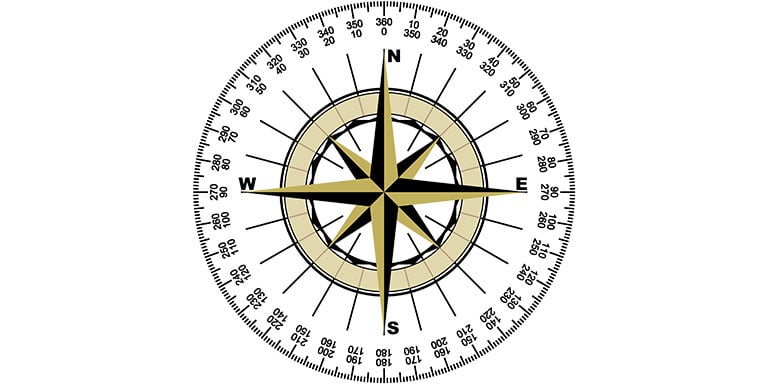

- Compass: You can get a basic one with degree markings (they're important) for less than $20.

- Waterproof map case and plastic overlay sheets: If you're going to practice map reading outdoors, make sure the map is protected from rain and moisture. Whether you're inside or outside, you'll also want some acrylic overlay sheets so you don't have to draw on the map itself.

- Pencil or marker: Depending on what you're drawing on, you'll need pencils or erasable markers.

- Compasses (drawing tool), ruler, and protractor: These are basic tools for calculating angles, circles and distance. You can buy a pack containing all three for a few dollars. You'll use them more for actual land navigation than for simply reading a map, but you may find them helpful to check your understanding as you practice.

- Small notebook: Map calculations can get slightly complicated, so you'll want a place to do simple math. It's also helpful to be able to review your past calculations in case you make a mistake.

Parts of a Map

Some highly specialized maps have features you won't see on most others, but all maps have a few basic things in common.

- The legend is the key that tells you what everything else on the map means.

- Look for a scale to see how much real-world distance is represented by certain units of measurement on the map.

- The compass rose is a diagram that indicates which direction is north.

- Maps designed for land navigation should have issue dates, which is useful for determining magnetic declination (more on that a bit later). Better, more expensive maps may have actual declination lines.

Map Reading Skills

Once you've gathered your basic supplies, study your map and get familiar with its various elements.

Orientation

Start by finding the compass rose on the map. Lay your compass on top of it, offset slightly so that you can see north on both. Rotate the map and the compass until both are aligned and facing precisely north. Be sure to keep the compass at least one foot away from metal and electronics, both of which can interfere with its heading. Particularly strong magnets can interfere from many feet away. Finally, you may want to face north as well; many people find that this makes map reading easier.

Take great care to orient your compass with maximum precision — being off by one degree translates to being off by hundreds of yards over a distance of ten miles.

Magnetic Declination

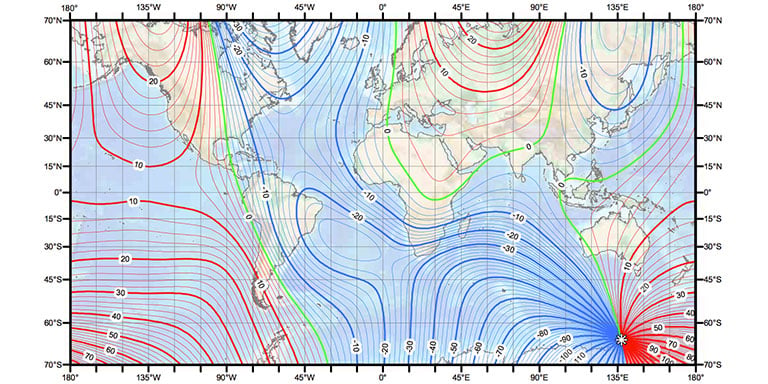

Also called magnetic variation, magnetic declination describes the difference between magnetic north and true north, which varies by location. It can even change over time, although annual changes are trivial — it takes decades for these small shifts to begin to have significant effects on map reading.

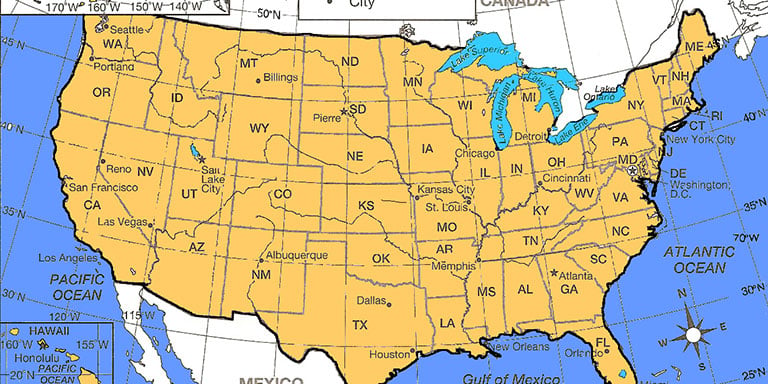

To read a map accurately, you'll need to know true north, which is likely a few degrees east or west of what your compass indicates. You can calculate true north if you know the declination value for your current location. The most accurate way to find it is by using an online calculator, but we're going old school here and assuming you're in the wilderness with no internet access. Your next best bet is to use a paper declination map. This could be a separate map of the country, but high-quality local maps also have declination lines.

Find your current position on the map, then locate the declination line closest to it. It will have either a positive or negative value; these values may be indicated on the line itself or the lines may be color-coded. Round to the nearest whole degree, then adjust your compass by that many degrees, remembering that declination is positive east of true north and negative west of true north.

If your map was printed within the last twenty years, you probably don't need to make any adjustments for time-related declination shifts. In most places on earth, declination lines shift about three degrees every hundred years, so if your map is more than twenty years old, you can use the following formula to get a rough estimate of how many additional degrees you need to adjust your compass:

(current year - year the map was printed) x 3

100

You should now have an orientation accurate enough to use for navigation.

Map Colors

Maps use colors to indicate various land characteristics, but there is no universal color code, so you'll need to refer to the map's legend or use context clues to figure out what its colors mean. Most commonly, land features above sea level will be portrayed in shades of green, yellow or brown. Those below sea level are often gray or red, and roads are typically black, red or purple. Blue represents water almost without exception, with darker shades indicating deeper water.

It's important to note that colors don't necessarily represent terrain types or vegetation. For instance, on many maps, much of the Mojave desert is green, but that doesn't mean it's covered in foliage (conversely, if a desert is colored brown or yellow, that's probably not because it's sandy).

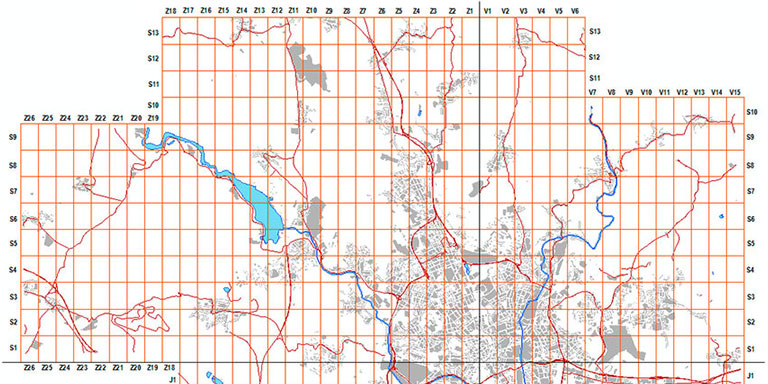

Grid Lines

On a map, grid lines are used to find and mark specific locations easily. Rows and columns will be marked with letters and/or numbers, used to reference the square formed where they intersect (e.g. “A3” or “GK”). When writing grid coordinates, always write the east-west or horizontal coordinate first. If you're using a book of maps, it will generally have an index of cities, roads, and other important landmarks, along with page numbers and grid coordinates to find them easily on the relevant map.

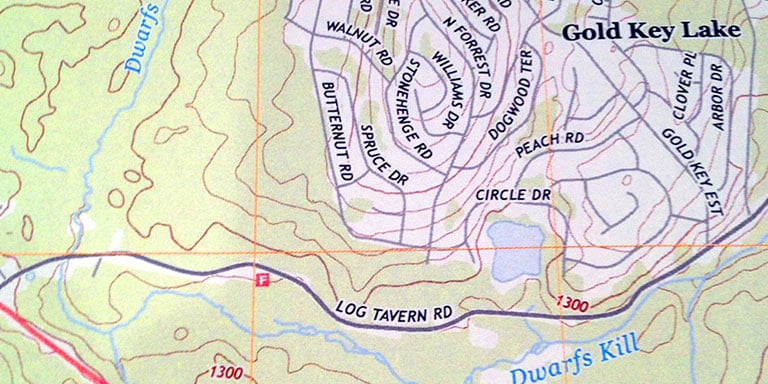

Contour Lines

Contour lines indicate elevation changes and are a bit trickier to read. They're easily identifiable as squiggly lines with numbers next to them, and they're almost always arranged in shapes approximating concentric circles. Each line or circle represents a consistent interval of elevation change, and you'll need to refer to the legend to see what that interval is. Many lines bunched close together means you're looking at a steep hill or mountain, whereas fewer lines spaced farther apart represent a gentler slope. The numbers next to or bisecting each line indicate the height above sea level at that point on the map.

On most maps, solid contour lines indicate increases in elevation and lines with dots or tick marks represent decreases in elevation.

Terrain Features

There are many types of terrain features, but if you know these eight, you'll be able to read most maps comfortably.

-

Hill

A hill is a point or area of high ground from which the ground slopes down in all directions. -

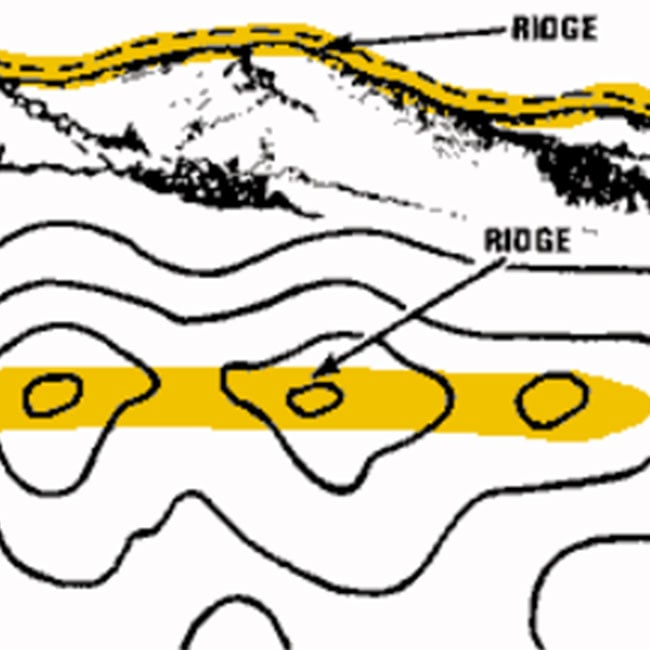

Ridges

Ridges are akin to a single, long hill with one contiguous top. All points along the top of the ridge are higher than the ground to either side. -

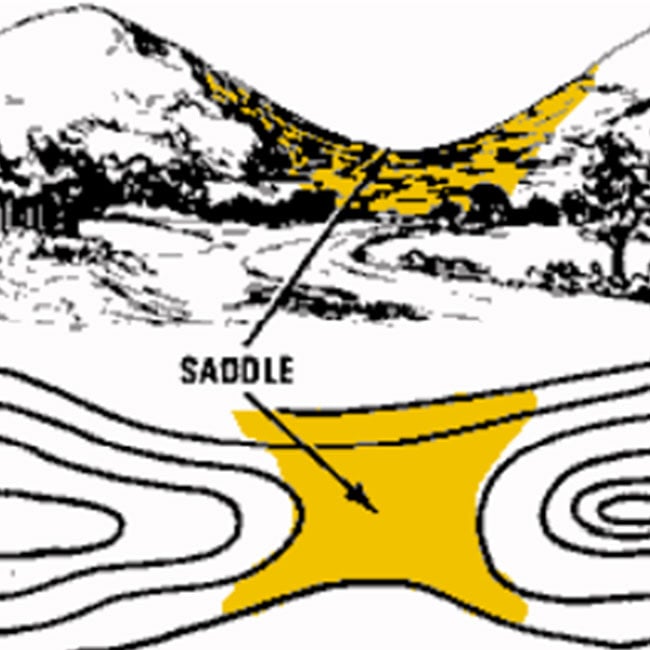

Saddle

A saddle is a dip or low point along the crest of a ridge. -

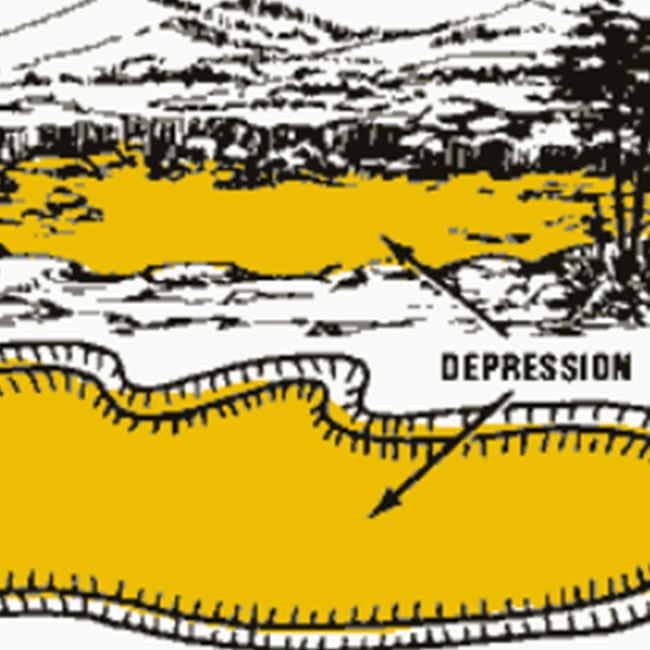

Depressions

Depressions are holes or low points surrounded by higher ground on all sides. -

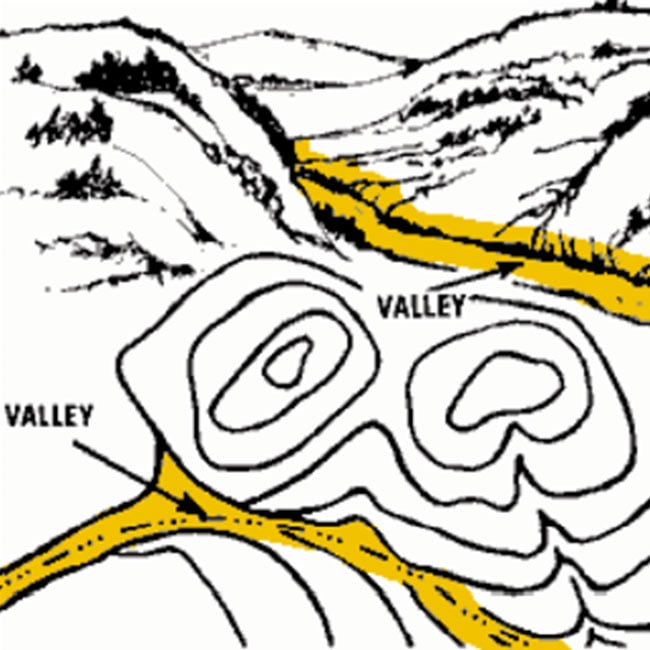

Valleys

Valleys are similar to depressions in that they're surrounded by higher ground but they're much longer and shaped more like riverbeds (some do contain streams or rivers ). Valley floors are relatively flat. -

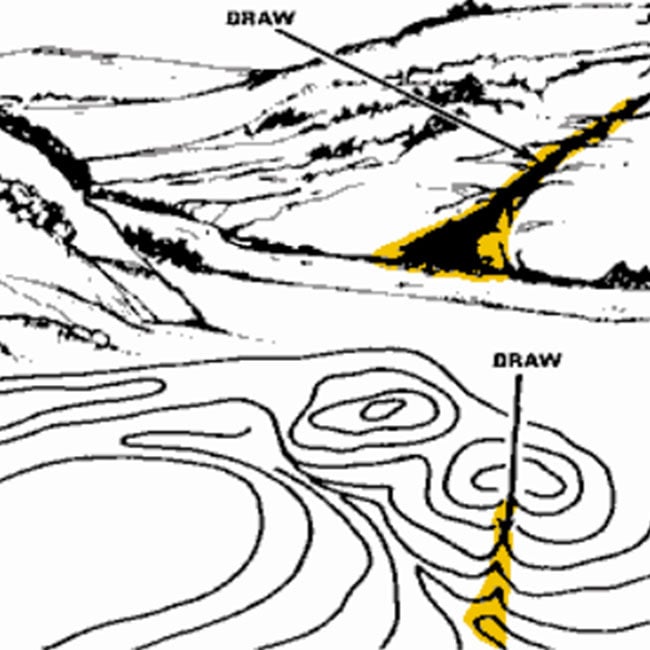

Draw

A draw is a downward-sloping channel or riverbed with an uneven floor. It's usually created by flash floods and is narrowest near the point of origin. -

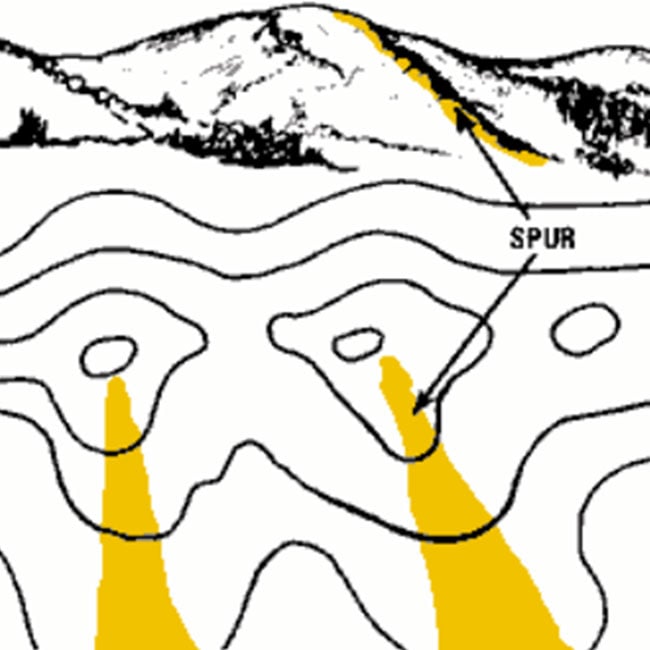

Spurs

Spurs are short, sloped sections of higher ground found on the sides of ridgers. They're usually created by parallel streams wearing away the terrain to either side. -

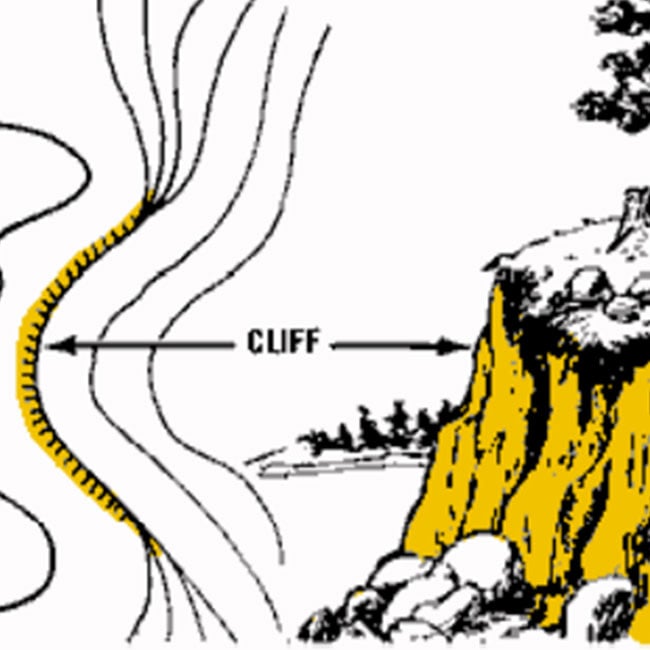

Cliff

A cliff is, of course, a vertical or near-vertical slope.

Latitude and Longitude

These lines are distinct from grid lines. Highly detailed maps of very small areas don't have them, but virtually all others do.

Latitude lines run east-west and longitude lines run north-south. To help you remember which is which, note that, on a map, horizontal LATitude lines look like a LADDER. The equator is zero degrees, and the north and south poles are both 90 degrees. Coordinates north of the equator are given in degrees north and those south of the equator are given in degrees south.

Longitude lines follow the same basic principle, with the prime meridian representing the zero degree mark. However, longitude lines go to 180 degrees in each direction, rather than 90. Coordinates east of the prime meridian are given in degrees east and those west of it are given in degrees west.

As you might suspect, latitude and longitude degrees alone aren't precise enough to locate a specific place on the planet — a single latitude/longitude grid square can encompass an area as large as 4,900 square miles. For this reason, latitude and longitude degrees are divided into sixty minutes, which are in turn divided into sixty seconds. You may find it helpful to memorize these commonly used reference numbers:

- 1 degree of latitude (written as 1°) = 70 miles

- 1 minute of latitude (written as 1') = 1.2 miles

- 1 second of latitude (written as 1”) = 0.02 miles or 105.6 feet

Note that these numbers apply to latitude only. This is because latitude lines are spaced evenly at any point on a world map. Longitude lines, however, aren't as easy to convert to physical distance. At the equator, 1 degree of longitude is also equal to 70 miles, but as you move north or south, 1 degree of longitude represents less and less distance because longitude lines converge at the poles. Your map may show precise longitude measurements for the area it portrays.

Once you understand how to read and write coordinates this way, identifying precise locations on a map is fairly simple. The center of Chicago, for instance, is located at 41°51'0”N 87°39'0”W, read as “41 degrees, 51 minutes, 0 seconds north; 87 degrees, 39 minutes, 0 seconds west.”

Compass Degrees

Compasses also use degrees, but these are not the same degrees you reference when calculating latitude and longitude. Compass degrees are used to identify a precise direction of travel, whereas latitude and longitude pinpoint a specific location on a map.

Cheap compasses don't have degree markings; these are more like toys than actual navigation aids, so be sure to pick up a compass that has proper degree markings. There will be 360 degrees marked around the circumference of the compass, usually in increments of five. Some compasses have degree markings only from 0 to 90 (i.e. from due north to due east). In such cases, you'll need to add 90, 180, or 270 degrees as needed to indicate southeast, southwest, or northwest headings, respectively.

In the context of map reading as distinct from land navigation, you'll most commonly use compass degrees to indicate the position of one point of interest relative to another. It can get awkward and imprecise to say “Point B is about 42 miles south-southwest of Point A,” so instead, you can simply say “Point B is 186 degrees, 39 miles from Point A.” This means that if you draw a perfectly straight line between these two points, it will represent exactly 39 miles and its angle will be exactly 186 degrees as measured from due north (on the map — not necessarily true north).

Maps are rich and complex things — hence, cartography is its own profession. Fortunately, you don't need to be a cartographer to read a map proficiently, and you should be able to do so once you've spent some time practicing the basic skills we've outlined here.

Did you find this article helpful?